Do I Still Love 1963's Winter Light?

1963 Svinsk Filmindustri

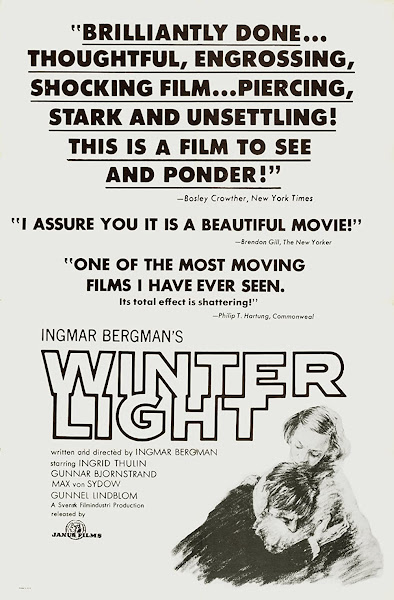

Written and Directed by: Ingmar Bergman

Starring: Ingrid Thulin, Gunnar Björnstrand, Max von Sydow, and Gunnel Lindblom

MPAA Rating: N/R; Running Time 81 Minutes

The Nicsperiment Score: 10/10

A rough-looking, worn out Pastor Tomas Ericsson leads Sunday morning service in his rural Swedish church to a mere handful of parishioners. He may have the flu, but there's a greater sickness in his soul. Ericsson is not only deeply depressed, but doubting his faith, even as he tries to lead his dwindling flock. One of his few members, Jonas, is fixated on the possibility of nuclear war with China, contemplating a suicide that would leave behind a wife and children. Another, Algot, really wants to plan a time to have a spiritual conversation with Tomas, though the tired pastor can't even feign interest. Most personally, a female church member, Märta, can't care less about religion, but does care for Tomas, with whom she's had an ongoing affair that seems to be on the rocks. As for Tomas, the snowy, lonesome landscape is a great stand-in for his heart, which has been seemingly irreparably broken since the death of his wife, years before. Can Tomas navigate his rocky journey of faith, keep his congregation from falling apart, and make some kind of life with Märta? Can he even make it to his own afternoon service? Perhaps most importantly, can he think of anyone but himself for one damn second?!

* * *

By the time I completed the audio-visual arts program at LSU, I hadn't seen a single Ingmar Bergman film. Still, the man's name kept coming up in my textbooks, and I spent much of the next year, 2005, diving headfirst into the sometimes difficult waters of his filmography. Often, I found that I greatly enjoyed his sensibilities, and that his films, in general, looked immaculate. There was one film of his I couldn't stop coming back to: 1963's Winter Light, whose Swedish title, Nattvardsgästerna, more accurately translates as "The Communicants." The film, the central entry in what is commonly regarded as Bergman's "faith trilogy," quickly shot up my "Favorite Movies" list until it was second only to Vertigo, which I recently discovered, is still my favorite film. On a modern rewatch, does Winter Light still hold its ground, as well?

|

| A broken shepherd |

I feel like a "favorite films" list should be constructed on the basis of unfiltered personal enjoyment. Just rattling off stuff that seems to be the most critically praised is redundant. With that said, as objectively great as I believe Winter Light to be, I do wonder if its religious focus may alienate viewers who have no interest in those pursuits. Its central quandary, "Should this broken, doubting man hold onto his faith?" might be met by atheist viewers with the simple response of "of course not, next question," but for this viewer who has sometimes doubted, but always kept his, this is a vital question, and a vital film. Please proceed at your own peril, as SPOILERS AND RELIGIOUS MUSINGS ENSUE.

|

| I am just realizing as I caption this how important this early image is to the end of the film |

The sight of the small, dull crowd, as Tomas goes about the ritual of communion, won't be an unfamiliar one to anyone who has been involved with a body of worship for an extended period of time. Sometimes, a particular church just gets sick or dies, and it's quite clear from this opening service that Tomas' dour lack of enthusiasm in delivering the holy eucharist, paradoxically the most joyful and sorrowful of sacraments, is the malignant phlegm in this church's slow death rattle. Tomas seems to have a lack of interest in anything but his own suffering. Often, Bergman's flawless compositions cast Tomas as the one on the cross in place of Christ. When the suicidal Jonas seeks spiritual encouragement after the film's opening service, Tomas can only bemoan his own pain and loss of faith, revealing that the central tenet of Tomas' faith is not Christ, but his own heartache. Why would anyone come to this man to find God?

|

| As Jonas, Max Von Sydow turns in a surprisingly defeated and downbeat performance |

Tantamount to Tomas' suffering is what he perceives as God's silence, and worst of all, silence at the time he needs God most. Instead of a loving God (explored in a head-scratching way in the trilogy's previous film, Through a Glass Darkly), Tomas can only perceive a horrific and uncaring spider God, before declaring to a baffled Jonas, in what was supposed to be an encouraging counseling session, that God does not exist. Jonas promptly leaves, drives down to the river, and blows his brains out.

Some pastor.

|

| Tomas is literally the devil on Jonas' shoulder |

Instead of the loving God he's given up on seeking, all Tomas seems to find is a loving Märta, who repulses him. In a stunning performance, Ingrid Thulin, top-billed in this film, imbues Märta with a desperate and longing persistence, not ever wanting to leave Tomas' side, even when he rejects and denies her. At this point in my analysis of the film, I need to say in regard to themes, there's what Bergman thinks he is doing, there's what a cold, interview-quoting film scholar thinks Bergman is doing, and there's what I can see and hear with my own eyes and ears. In this film, the atheistic Märta, who loves Tomas unconditionally, despite his faults and despite his doubt, is a clear stand-in for God, or more specifically, the Triune Christ.

|

| I'm finding in these rewatches that plentiful thematic layers are my catnip |

Thulin's famous monologue scene, where Tomas reads a letter from Märta that's presented to the viewer rather famously as a stunning, nearly unbroken still closeup of Märta's face, reveals that at one point Märta even suffered from a rash that was essentially stigmata. Ironically, this physical infliction repulsed Tomas all the more. In this very multi-layered film, there's also a parallel in the rejection Tomas feels from God and the rejection Märta feels from Tomas. Ironically, Märta is the only character who prays hoping God will hear her, her heartfelt pleas a stark contrast to Tomas' cold and robotic recitations. Märta even admits in disbelieving belief that she asked God for a task worthy of her strength, and God answered by giving her the impossible task of Tomas. She also ends the film with a prayer, "If only we could feel safe and dare show each other tenderness. If only we had some truth to believe in. If only we could believe."

|

| Four more hours of this, please |

As Tomas, Gunnar Björnstrand gives a flawlessly natural performance. As a 23-year-old living with his parents and trying to figure out his life, I found this self-obsessed central character who is far more focused on his own pain than the suffering of others far more likable than I do now as a 40-year-old with a family. Tomas' self-centered, woe-is-me attitude is execrable, particularly in the scene were he turns Jonas' counseling session into his own dark, personal confessional. That this character is still an engaging, relatable presence is not only a testimony to Bergman's writing and direction, but to the craft of Björnstrand, who is playing against type.

|

| Holy Connection |

Before I partake in the film's strongest element--its conclusion--I must praise the close runner-up. Bergman sets this film in one day, over six hours which roughly correspond with the hours of Christ's crucifixion. The opening morning service scene corresponds with the moment Christ went on the cross around 9 am, and the 3 pm afternoon service Tomas is holding in an even more remote and forlorn town corresponds exactly with the time of Christ's death. Bergman even makes sure we get several shots of a clock (and there's a quiet ticking throughout most of this rather quiet film), so that we generally know what time it is in any given moment of the film. It's this attention to detail, along with the film's brisk 81-minute runtime, which helps create a slice-of-life, lived in, moment in time feeling that I'll always find entrancing. Add to this the constant attention to Tomas' bitter cold, enhanced by his constant coughing, Björnstrand's incredible body language, and each character Tomas encounters remarking about how sick he looks, and I personally feel I'm transported to a winter day in the rural village where I was raised. Glynn, Louisiana, when we actually get a winter, minus some of the distant rolling hills, feels remarkably like the setting here. There's a moment near the end of the film, just after he's identified Jonas' body for the police, where Thomas ventures into Märta's empty classroom (fittingly, she's a teacher). As he sits at a desk in the one-room school, waiting for Märta to bring down cold medicine, iced-over fields giving way to unknowable forests outside, I feel at home. Hey, there's a reason bias is inherent in the word "favorite."

|

| Might as well be parked between Joni Jarreau's barn and Lakeland Elementary |

The schoolhouse scene leads into an even more disastrous conversation with Märta, where Tomas completely and totally rejects her. Tomas then must break the news of Jonas' death to his widow, Karin, who can barely hide her contempt for Tomas as she rejects his invitation to pray. Märta rides with Tomas to the second church and the film's conclusion, immediately taking him up on his offer to join her just moments after he confesses how much he despises her. The two must stop for a moment to yield to a train full of coffin-shaped cars. The film scholar on the Winter Light Criterion Collection commentary declares that this is clear symbolism of the death and rejection of Bergman's own religious faith. I find this to not only be an alarmingly literal interpretation of this cinematic genius' visual language, but also, profoundly stupid. Bergman was never able to get away from his religious inclinations. Even if Bergman said that every film he made after this trilogy moved into the realm of human relationships and away from humanity's relationship with God, holy shit is God there in every single one of those films, even and at times especially by His absence. This is also, if anything, belied by comments by Bergman's close acquaintances, who seem to imply that Bergman was still seeking and toying with religious ideas up until his death. The most simplistic reading of perhaps the greatest writer and director to have walked the Earth's self-proclaimed favorite film he ever made is, "Winter Light is about someone losing their faith," and I encourage you to doubt any critic who reduces this complex, nuanced, and spiritually transcendent film to a mere math equation. Winter Light's multi-layered final scene proves that Ingmar Bergman was anything but settled on such simplistic terms.

|

| I pray for better film criticism |

Tomas and Märta arrive at the church just before service is set to begin, and find that not a single parishioner is in attendance. Only the faithful Algot, who ironically, takes physical care of the church property and handles both the lights and church bells, and the debauched, there-for-the paycheck organist, Fredrik, are waiting within. Much has been made of the fact that Bergman's father, Erik, was not only a Lutheran minister like Tomas (chaplain to the King of Sweden, no less!), but that Tomas' last name is literally Ericsson. Maybe this is a clear hint that "Erik's son" is not like his father and full of doubt, or maybe Bergman saw the chance to reference his father and just couldn't resist. Whatever the case, Tomas Ericsson heads to the back room of the second church sick, exhausted, and fresh off of angrily denouncing God's existence, as he toys with the idea of cancelling this unattended service altogether. Algot follows Tomas there, reminding him that the two had something to discuss. Algot, who suffers from an extreme case of rheumatoid arthritis, and walks with a severe limp, had apparently been having trouble sleeping. Tomas had previously recommended that Algot read the Gospels to help him fall asleep, and this solution seems to have mostly worked. However, these readings seem to have also led Algot to an epiphany regarding Christ's crucifixion.

|

| I feel like maybe this Bergman guy can compose a shot |

|

| Every movement within the frame is poetry |

|

| And every closeup is divine |

In the film's key scene, Tomas sits inattentively before being slowly being drawn in by Algot's spiritual discovery, which I include here in its entirety:

"This emphasis on physical pain. It couldn't have been all

that bad. It may sound presumptuous of me - but in my humble way, I've

suffered as much physical pain as Jesus. And his torments were rather brief.

Lasting some four hours, I gather? I feel that he was tormented far worse on

an other level. Maybe I've got it all wrong. But just think of Gethsemane,

Vicar. Christ's disciples fell asleep. They hadn't understood the meaning of

the last supper, or anything. And when the servants of the law appeared, they

ran away. And Peter denied him. Christ had known his disciples for three

years. They'd lived together day in and day out - but they never grasped what

he meant. They abandoned him, to the last man. And he was left alone. That

must have been painful. Realizing that no one understands. To be abandoned

when you need someone to rely on - that must be excruciatingly painful. But

the worse was yet to come. When Jesus was nailed to the cross - and hung there

in torment - he cried out - "God, my God!" "Why hast thou forsaken me?" He

cried out as loud as he could. He thought that his heavenly father had

abandoned him. He believed everything he'd ever preached was a lie. The

moments before he died, Christ was seized by doubt. Surely that must have been

his greatest hardship? God's silence."

|

| My favorite bit of dialogue from any film |

In this moment, Algot converts Tomas to Christ. Depending on your theology, you could even say he reconverts him. You can see the moment of epiphany on Tomas' face as Algot reaches his thesis, made even more explicit when Tomas announces, after concurring with Algot, that church will indeed be held. To be honest, Algot converted me, as well. This is likely the point that I'll lose the majority of my readers, who will see I had a chance to join them in their non-belief, but chose otherwise, and who might remark, "That's too bad, well good luck with that," to which I'll quote one of my favorite Christians, Norm Macdonald, and say "Good luck for you too. It's not like your idea of being thrown in the ground and having dirt tossed on you is such a beautiful, great idea." Any layman knows that Thomas was the Apostle who doubted--but any true layman will also know that the same Thomas' faith was restored. If you want to stop reading now, that's fine. But I have one more paragraph.

|

| Algot, the Evangelist |

At one point in life, regardless of my wife, regardless of my then young child, I felt completely alone, and more depressed than ever. I felt like the dark emptiness of the universe was dead-set against me, as I watched all the works of my hands crumble into nothing, watched as anything that I could hope for, even the most simple things, went awry or against the direction I had hoped. I felt completely abandoned by God as my prayers floated seemingly unheeded into an infinite and uncaring void. I remembered hearing "Jesus can understand anything you're going through" so many times and thinking "bullshit." Then I watched this film. Thanks to Bergman, I felt akin to Christ because I realized that Christ once felt abandoned by God as well, which ironically, through the mystery of the Triune God, helped me to again feel the presence of the Father. I'm sure this was not Bergman's intention as he formed this film in the freezing Swedish winter, but he created such a transcendent work in Winter Light, God could work through it to reach me approximately 50 years later in a sugar cane field in South Louisiana. That's the connecting power of the magic of cinema, and the quite biased reason Winter Light is still a close runner-up as my favorite film.

Comments