Do I Still Love 1960's La Dolce Vita?

1960 Cineriz

Directed by: Federico Fellini; Written by: Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano, Tullio Pinelli, and Brunello Rondi

Starring: Marcello Mastroianni, Anita Ekberg, Anouk Aimée, Yvonne Furneaux, Alain Cuny, Annibale Ninchi, Magali Noël, Lex Barker, Jacques Sernas, and Nadia Gray

MPAA Rating: N/R; Running Time: 174 Minutes

The Nicsperiment Score: 10/10

Marcello Rubini is a tabloid journalist in 1960's Rome. Conventionally handsome and seemingly well-respected by those around him, Marcello appears to have it all: a beautiful girlfriend, wild nights with celebrities, long talks with vaunted intellectuals, unlimited access to the rich and the famous, mistress after mistress. However, the harder Marcello chases happiness, the foggier the path becomes. The more he seems to find someone who has the world figured out, someone he can perhaps join with, possess, or emulate, the less anything makes sense. As the gulf widens between the life Marcello idealizes and the life he actually sees before him, will he fall into the nihilistic darkness of senseless debauchery, or will Marcello find some meaning to life beyond empty hedonism and vaporous symbols?

|

| I either just piqued your interest or bored you to tears! |

At the start of the spring semester of my junior year of college, I had a late-afternoon doctor's appointment that changed my entire outlook on life. I then trucked it to the first lecture in my one-night a week Italian cinema class. On the drive to school, I got into a frustrating argument with my mother about the outcome of the appointment, then ran to class and snuck in the back, just as a black-and-white helicopter, carrying an enormous statue of Jesus, flew across the giant television screen in the Allen Hall classroom. The next three hours changed my life even more than the preceding doctor's appointment, as Federico Fellini's La Dolce Vita brought me a cinematic joy few other films have elicited in the last 20 years of my life. The themes, the sense of life, the camera movements, all of it felt so new, so perfect, so archetypal of some eternal thing that oxymoronically has never before or since existed. I immediately elevated 1960's La Dolce Vita into the four-spot in my top five favorite films list...but 20 years after that rapturous first viewing, does La Dolce Vita still hold that sweet spot in my heart?

|

| Hey, if you've made it this far, you might as well read to the end. And it's English, I swear! Louisiana English! |

La Dolce Vita is split into seven loosely connected episodes, and features a prologue and epilogue, and a bisecting intermezzo that at first seems a respite from the rest of the film, but comes back to matter in the end. For me, everything matters in this film, though in multiple viewings over these last 20 years, I'm still parsing those things out, and likely always will be. The prologue is the aforementioned statue of Jesus scene, where Marcello's news helicopter follows the statue-carrying helicopter, until Marcello and his fellow passengers are distracted by a group of beautiful, sunbathing women. They fly over to the sunbathers, and in a moment that might function as a codex depending on your final takeaway from the film, Marcello attempts to communicate with them, but everyone's voices are droned out by the sound of the helicopter, and no one can hear anything anyone is saying. Marcello's helicopter gives up and leaves.

|

|

I think it's important to note that the opening shot features the

helicopters bringing Jesus past landscapes of antiquity... |

|

| But Marcello's helicopter veers away toward the malaise of modernity in the next shot, as Jesus heads in a different direction |

The first episode now formally introduces the viewer to Marcello in profile, as he puffs away at a cigarette in an fancy nightclub. The journalist appears to be master of his domain, as everyone around him seems to defer to and respect him. He bumps into an apparent acquaintance, a beautiful socialite named Maddalena, and the two leave for a joyride. They park Marcello's very nice car in an area frequented by prostitutes, offer one a ride home, then have sex at the prostitute's apartment as she makes them coffee. Marcello then rides home that morning feeling pretty high on himself, only to find that Emma, the fiancée he left back home, has overdosed. Marcello rushes Emma do the hospital, where she recovers and he expresses undying love for her, then rushes to a phone to call Maddalena, who misses the call because she's sleeping off the previous night.

|

| The King of a House of Cards |

So much is established in this opening episode, including the film's general structure, as every following episode has both a night and dawn segment. Marcello's character is also clearly drawn. On paper, his actions sound a bit abhorrent, but in action, he is highly relatable. A lot of that is due to Marcello Mastroianni's incredible, naturalistic performance (yes, playing a character named Marcello). Mastroianni's charm, charisma, and paradoxical pairing of intelligence and dopey cluelessness almost give the film a documentary feel, bolstered by Fellini's direction and the script, both of which tightly tie Marcello to the mast of the HMS Human Condition, as it is floundering in a sea of senseless modernity. This episode also sets a visual motif of "construction," as the outskirts of Rome, often pictured in the "daylight" segments of the film, are generally rural areas with new high-rise apartments springing up from the dust.

|

| That documentary would have to be titled Three Hours of Perfect Shots |

The second episode is likely the film's most well-known, and certainly a standout. It begins with Marcello arriving at the airport with other tabloid journalists for the arrival of a famous Swedish/American actress named Sylvia. Fellini wastes no time revealing that Sylvia is a vacuous cypher, a physically stunning, yet vapid woman whose wild, instinctual nature borders upon the feral. As the mass of reporters and photographers fawn over Sylvia and the welcoming committee shoves pizza in her face, Marcello hangs back coolly, until, like Fellini's camera, the soundtrack, and the viewer, Marcello is sucked into Sylvia's endless, enigmatic void of animal magnetism.

|

| There he goes again... |

First, Marcello is the only reporter physically (and perhaps mentally) fit enough to follow Sylvia's breathless climb to the top of St. Peter's dome, and the two nearly kiss before a sudden wind blows Sylvia's hat away. Then, at a late-night party, Marcello and Sylvia dance and the hapless Marcello begins to spout and superfluous stream of romantic hyperbole at Sylvia. The party soon spirals into madness, as one of Sylvia's wild actor friends arrives, a conga line starts, and the partygoers build into a frenzy, before Sylvia's drunken fiancé insults her, and she leaves the party with Marcello.

Marcello and Sylvia drive the countryside only to return to the dusky, empty streets of Rome. Sylvia finds a kitten and puts it on top of her head, while Marcello runs off to find some milk. In the film's most iconic moment, Marcello returns to find Sylvia dancing in the roaring Trevi Fountain (the forgotten kitten stands a safe distance away, and Marcello gives it the milk). Marcello enters the fountain, raises his hands in near worship to Sylvia, idealizes her closed-eyed face like a renaissance painter, and it seems he is on the verge of some eternal secret, the answer to some universal mystery of human connection as their faces near, then the fountain shuts off, the rising sun peaks over the building tops, and the moment is lost in a deafening silence, just before the climactic revelation of epiphany. Marcello brings Sylvia back to her hotel, where her fiancé slaps her and tells her to go to bed, before giving Marcello a beating.

|

|

It's almost absurd... |

|

|

...how Fellini can show me as a viewer how vacuous and empty Sylvia

is... |

|

|

...then seduce me so deeply... |

|

|

...I'm convinced the key to life is in her lips... |

|

| ...only for him to pull it away in yet another moment I'll be analyzing for the rest of my life. |

In a third episode that's broken up between the others, with the idiosyncratic imagery of a woman posing for photographs with a horse behind Marcello's gleaming car, our protagonist runs into Steiner, an intellectual friend that Marcello idealizes. The two enter a church, where Steiner humorously plays jazz to gently ruffle the priest's feathers, before launching into Bach. This leads directly into the fourth episode, where Marcello and Emma drive out to the countryside to visit the site of a purported miracle. The details of the miracle, a sighting of the Madonna by two children, are sketchy at best, and lest it appear that Fellini is taking a stab at what I might describe as "true religion" here, a disbelieving priest says, "Miracles come from pious meditation, from silence," ironically the things to which Marcello seems most allergic. As huge crowds arrive and the rain begins to pour, the two children run around shouting "there she is" as the masses work themselves into a frenzy, eventually trampling a sick child to death and tearing apart a holy tree. Before the episode ends in a somber morning, the children declare that Mary will never return unless a church is built in this location, as Emma prays to the same Mary to have Marcello's true and undying love.

|

| One of the few moments Fellini overtly suggests a solution to Marcello that won't end in misery. Don't worry, though, it's in one ear and out the other. |

The film then dives into the meat of the third episode, and perhaps the film's most perplexing. Marcello and Emma attend a party of intellectuals and bohemians at Steiner's luxurious apartment. Steiner, seemingly happily married, with two young children, is revealed to be split in his passions. Emma sees Steiner's domestic side, and assures Marcello that one day he can have that with her, but Marcello seems less than enthused by the idea. In a private balcony conversation with Marcello, Steiner reveals he is not completely partial to this side of his life. Steiner loves his family, but at the same time, he finds the security in family and financial stability stifling. He theorizes that a life of instability might actually be more spiritually uplifting, yet laments at his children's future, fearful of what world might await them. This aspect of the character, in a way, mirrors the character of Jonas in my second favorite film, Winter Light. If all these contradictions weren't enough, partygoers give Marcello incredibly conflicting information in contradictory platitudes like, "Stay free, available, like me. Never get married. Never choose. Even in love, it's better to be chosen," as they listen to recorded nature sounds from the sterilized environment of Steiner's apartment.

|

|

Once you've seen La Dolce Vita all the way through, these

scenes in Steiner's apartment become so much more haunting... |

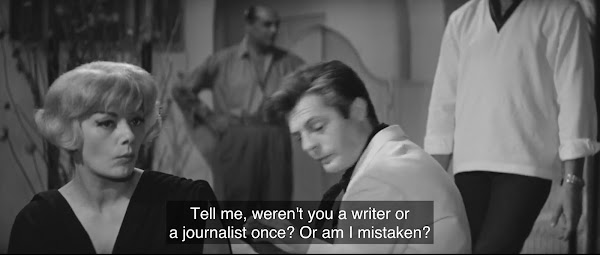

A small throughline in the film involves Marcello's artistic and professional aspirations. Apparently, Marcello is an incredibly talented writer, a fact known by his colleagues, who often wonder why Marcello is wasting his time in the sewers of tabloid journalism. All of the intellectual conversations at the party seem to reawaken Marcello's loftier ambitions, and in the films intermezzo, essentially a brief middle chapter eye of the storm, Marcello attempts to write at a quiet seaside restaurant. However the waitress keeps playing music, Perez Prado's cha-cha, "Patricia," and Emma distracts and berates his absence to him over the phone...in calls he himself initiates.

|

| Then do it! |

As Marcello tells the waitress to turn off the music, he suddenly finds himself, briefly, in the presence of something holy. The waitress, a teenaged girl named Paola, seems untouched by the rest of the world. It soon becomes apparent that Paolo transcends any simple meaning with which Marcello can define her. His interest in her is (thankfully) not sexual, but in what she might represent. Fellini doesn't spell out the symbolism, but it's clear from Paolo's manner, in the way she dislikes the hubbub of Rome and misses her small town, the purity in the way she continues to sing "Patricia" after the music stops, and in Marcello's comparison of her to an angel, she represents a divine escape from the endless noise of Marcello's current lifestyle. Unfortunately, Marcello's takeaway from the encounter is to push aside his typewriter and yet again call Emma.

|

| Sanctum |

The fifth episode is a bit Dickensian in a sort of "Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come" way, as Marcello's father comes to visit, and the two have a night out on the town with Marcello's colleague, Paparazzo. Paparazzo is La Dolce Vita's enduring gift to modern parlance, as our modern "Paparazzi" is indeed named for his character. The trio end up at a nightclub that Marcello's father visited in his youth, and it soon becomes clear, as Marcello is suddenly hit by memories of his father's frequent absence throughout his childhood, along with memories of his mother's tears, that the old man once lived a partying lifestyle much like Marcello's.

|

| I wish this film was more beautiful... |

|

| ...but that would be impossible. |

Fellini works miracles in this segment, presenting a feast of sight and sound that is both intoxicating and piteously wistful. Marcello sees Fanny, one of a cavalcade of his ex-girlfriends, dancing at the club, and calls her over. Marcello's father immediately strikes up a romantic chemistry with her, and the two dance and eventually leave together. Marcello later drives to Fanny's apartment to find Fanny standing outside, panicking. Apparently, Marcello's father has had a minor heart attack, and Marcello sends Paparazzo off to get medicine. Marcello enters to find his father dressing and brushing off medical assistance. Marcello begs his father to spend the day with him, but his father brushes him off, as well, insisting that he must go home, leaving behind a dejected Marcello.

|

| A shadow of a man |

The penultimate episode sees Marcello spending his night on the Via Veneto, the luxurious Roman street frequented by celebrity and paparazzo that acts as Marcello and the film's damnable home base. Marcello ends up riding out to an aristocrat's castle with a bunch of hard-partying rich, famous, and inebriated friends and tenuous acquaintances. He runs into Maddalena at the castle, and the two engage in an encounter that make several of the film's themes explicit. The duo run off together, and Maddalena forces Marcello to sit in a chair in an empty room with his eyes closed. Maddalena then flees to an echo chamber, from which she engages Marcello in conversation. Eventually, she asks Marcello to marry her, but his response from the distance of the echo chamber is diluted by doubt, as he spouts romantic platitudes (gentle reader, consider yourself lucky I haven't used "platitude" more here, as this is fittingly how many of the characters in this film speak).

|

| Maybe you never really did? |

While Marcello babbles on, another man approaches Maddalena, the two embrace romantically, and Marcello, clueless at Maddalena's silence, babbles on a little longer, then rejoins the rest of the group. In perhaps the film's most haunting sequence, the partygoers go ghost-hunting in a nearby abandoned villa, and as Fellini embraces the scene with some of his most enrapturing camerawork and technique, Marcello is seduced in the candlelight by a British heiress visually reminiscent of Lily Munster, and the two spend the night together.

|

| Generally, anytime someone looks directly at the camera in this film, it's a little terrifying |

This night segment of this episode feels a bit like a descent to the grave. The day segment sees the exhausted partygoers making their way back to the castle. They cross paths with the lady of the house, who is walking to mass with a procession of priests, in a moment fittingly reminiscent of the closing segment of Fantasia, after Night on Bald Mountain. This sense of horror continues on the soundtrack, as the film segues to the closing segments of the interconnected third episode, to a quiet, yet persistent and menacing organ drone, reminiscent of Bernard Herrmann's work in the haunting stalker segments of my favorite film, Vertigo. Marcello and Emma violently argue on a late night road, just past the outskirts of town. He parks the car and eventually kicks Emma out, but not before this gem of a toxic exchange:

Emma: Some men are happy when they find someone who really loves them. Only you are like this! How terrible! How unfortunate!

Marcello: I really am unfortunate! My greatest misfortune was to have met you.

Emma: Who will love you as I do?

Marcello: I can't spend my life loving only you.

Emma: You're always miserable and unhappy.

Marcello: Don't you see you want me to lead a miserable life? All you talk about is cooking and the bedroom. A man who accepts that is nothing, do you understand? He just becomes a worm! I don't believe in your aggressive, clingy, motherly kind of love!

Rather interestingly, an enormous stadium light off in the distance illuminates the scene, as if the entire moment is performative. The night time portion of this episode fades to dawn, as Emma walks down the side of the road, Marcello races up to her in his car and opens the door, Emma gets in, and they race away. Cut to the co-dependent and awful couple in bed immediately after a passionate intimate encounter, Marcello clinging to Emma, their hands clasped, his head nestled at her breast. And then the phone rings.

|

| It's incredible how Fellini can make a shot of two attractive people in bed feel so disgusting and degrading. |

The dawn segment of episode three is the film's most shocking, as Marcello is called to Steiner's apartment to find police blocking access to the building. Marcello is allowed inside, and makes the awful discovery that Steiner has shot himself and his two young children in a murder/suicide. Marcello is stunned, unable to provide the police with any coherent answers. One of the policeman play back a now rather ominous recording from the recent party, where a guest tells Steiner he's as primitive as a gothic steeple so high up he "cannot hear anyone's voice," to which he responds, "If you could see me as I really am, you'd see I'm no higher than this" as the newer recording ends, and the older recording beneath it of ominous thunder rumbles. As Marcello wanders out in a stupor, Steiner's unknowing widow gets off the bus, crowds of paparazzi surrounding her and snapping pictures of her quizzical expression. A police officer begs Marcello to ask his colleagues to leave, but he can't utter a word, just barely managing to help the police guide the new widow to the car, before he himself stumbles in on the other side. As the car pulls away, photographers chase behind, still snapping photos, the segment ending with a satisfied Papparazzo walking toward the viewer.

|

|

Same shot...far different meaning

|

|

|

Heartbreaking. I've felt this moment more as I age, every time I

watch the film. |

|

| As empty a view as there's ever been |

Somehow, though, Steiner preferring a quick bullet to his and his offspring's heads over a lifetime of facing the troubles of the world with them doesn't feel like the most tragic event in the film. After all, this is Marcello's story, in which Steiner is naught but a symbol. The final episode, seven, moves into a future an unknown distance away. Marcello, now with grey streaks in his hair, has quit tabloid journalism not for a loftier ambition, but for one somehow even more grotesque and loathsome: a publicity agent. Throughout the film, Marcello has generally given in to his worst impulses. He cheats on his fiancée, then calls his mistress from the hospital after re-committing his love to his fiancée. He stays in a destructive, codependent relationship with that fiancée, which is obviously terrible for both parties involved. He also forsakes his formidable writing talents to focus on tabloid journalism. Now, after life has continuously given Marcello hints as to which directions he should take, and which directions he should not, our protagonist has thrown away all promise, any hope for a spiritually worthy life, for one of absolute filth.

|

| But hey, at least now he has an even nicer car... |

The chapter starts with an incredible, car-mounted tracking shot of vehicles racing down a dark highway toward the camera, engines roaring, headlights blinding. Marcello now drives an even gaudier white vehicle, and his current group of friends, acquaintances, and hangers on are so insufferable, they make his previous group look like the cast of Cheers. Marcello and his crew want to celebrate their friend Nadia's divorce. To do so, Marcello decides to ram his car through Nadia's now ex-husband's gate, as annoyingly child-like women hang off his hood and announce, in English, "Hi! Here we are!" Marcello then throws a rock through a house window, his gang of partiers march in, and a night of bored debauchery begins.

|

| While the film contains a few very subtle nods to horror, none are more overt than this creepy shot of the awful revelers looking through this mansion's windows |

The partygoers mostly sit in a bored, indifferent stupor, as if they've maxed out every sensation and can no longer be stimulated by anything...have I mentioned yet how modern this 1960 film is? Marcello tries to stir up the crowd. They decide someone should perform a striptease, but they've seen every naked angle of first volunteer. Finally, it is decided that Nadia herself should strip for everyone, and without much argument, she concurs. Her routine does little to drum up interest, except for some criticism ("she took off her bra too early"), and at the moment that her she's finally naked, her ex-husband, Ricardo, arrives home. Ricardo says everyone needs to be out in 30 minutes because he's got to leave again early that morning, but the aged Marcello refuses to let the party end. He berates his fellow partygoers and tries to incite an orgy, rides on a crawling, wildly inebriated woman's back, and then pastes pillow feathers to the same woman's face after water is spilled on her. In a sick perversion of the film's holy intermezzo, and in a hint of the film's coming conclusion, the record played by the partygoers over this bacchanal is Perez Prado's "Patricia."

|

|

Is it just me, or is the near feral partygoer on the right, who

wears a little girl's pajamas, the most annoying character in any

movie ever? Just look at her! |

|

|

As Marcello berates the partygoers, he's essentially berating

himself. I'm not sure if he says "no" once in this entire film. |

|

|

How tragic that Marcello once told his fiancée that an over-domesticated man is a worm, only for him to later become a worm of

an entirely different sort. |

|

| However, nothing is as tragic as the moment the older Marcello is asked this |

As Ricardo finally orders everyone to leave, and the rising sun begins to peak through the windows, a bitter Marcello continues to pull feathers from the pillow he's torn open, raining them down on each partygoer as they make their exit. Finally, in an obvious, and yet ingenious and affecting metaphor, the pillow runs out of feathers, and Mastroianni does his most brilliant bit of acting, Marcello's eyes hollow, his face worn, youth spent, hopelessly resigned to this downward spiral, as he lowers his head and walks out the door.

|

|

Have mercy, Fellini |

|

|

Just absolutely brutal |

|

| One of the finest actors of the 60's in his finest performance |

In an epilogue that grotesquely mirrors the prologue, Marcello and the partygoers wander through some nearby trees to the beach, where some fisherman are pulling something out of a net. As Marcello slowly stumbles at the back of the group toward the water, his nearest colleague excitedly assures him, "By 1965, there will be complete depravation! My dear, you can't imagine what filth will come out of it all." It turns out the fisherman have caught some sort of piscine monstrosity. "Get back!" one of them yells, "This fish is worth millions!" "Hey, come and see the monster!" shouts one of the partygoers, directly to the camera.

|

| Zombies |

|

| For me, this is the key shot of the film. There's a reason Fellini had this actress directly address the camera--she's essentially selling this entire film to the viewer. |

In the opening segment, Marcello and his colleagues detour from following a statue of Christ to flirt with sunbathers who can't even hear their voices. Now we see a horrific antichrist, surrounded by his own fishermen disciples who want to sell him for all he is worth. "Go back and get the camera!" someone urges, as another says, making the religious connotations more explicit, "It's been dead for three days." "It's still staring," Marcello says dreamily, as the camera focuses on one of the beast's glassy, incomprehensible eyes. Suddenly, something in the distance catches Marcello's eye, and he walks away from his entourage.

|

| It looks kind of disappointed |

The angel has returned, beckoning Marcello from across a shallow estuary. Paolo, years older, yet unchanging, calls to Marcello, waving him toward her. Marcello puts his hands to his ears. Over the ocean waves and wind, he can't understand a word Paolo is saying, fails to communicate, just as he did with the women in the opening scene, just as nearly everyone in this film has as they've talked at and failed to listen to one another. Paolo accepts that Marcello not only isn't ready to understand her, but can't be bothered to walk across the shallow estuary to reach her, though he's thoughtlessly waded through filth the entire movie. He's even waded into the Trevi Fountain for nothing more than a kiss with a starlet. Anything positive thing that requires even the smallest amount of work, even redemption, seems too much to bother about, though. Marcello gives a faint smile, waves goodbye, takes a female partygoer's hand, and is pulled away. In the final shot, Paolo waves, returns a well-wishing smile, then looks on enigmatically as the movie fades to end credits.

|

| Just too far to walk for this pitiable supplicant. Notice the shape in the backdrop. |

I'm no longer sure what my thematic takeaway of La Dolce Vita was back in 2003. I was seduced by its aesthetics, its absurdly beautiful tableaux, its constant stream of wonderful music and reoccurring themes, the incredibly singular liveliness and lived-in feeling of the film. Back then, I often said out loud, after finishing a particularly incredible film or book, "Damn," and I know I did so after this one, in front of all my new classmates. However, I think my younger, more nihilistic self left the classroom thinking that the eternal truth conveyed by La Dolce Vita is that communication is impossible. "With age comes wisdom" might be a platitude, but it's also a generally accepted fact. Now, I am not in any way saying that I, The Nicsperiment, am wise, but I do believe I can give a more nuanced take on this film as a 41-year-old than I could as a 21-year-old.

|

| Give it a few years |

Fellini has a lot to say here. Something key to the film, which I didn't notice 20 years ago, is the way the prologue and epilogue act as inverses. At the start of the film, Marcello forsakes truth and spiritual purity (the religious symbol of the Christ statue) for a base distraction (flirting with sunbathers). However, his attempt to communicate with that distraction fails. I'm not saying that La Dolce Vita is positing Catholicism as truth and spiritual purity, simply that the statue of Christ Marcello is distracted from represents that. The proof that the statue is a symbol of truth and spiritual purity, in a near thematic catch-22, is that Marcello does not pursue it, as this is an act he is repeatedly shown to be incapable of performing over three hours of screen time.

|

| "Look up, dummy!" |

Marcello, who has literally descended from the heavenly heights, the sky, at the start of the film, to the lowest topographical point, sea level, by the end, is pursuing a symbolic antichrist with his debaucherous friends. The beast from the sea, which had been dead for three days, just as Christ was in the tomb for three days, has now made its revelation known to the world, and is now an object of unholy spectacle, to be exploited for profit and fame. Marcello is then distracted from this antichrist by another symbol of truth and spiritual purity, Paolo, with which he fails to communicate. He has experienced so much depravation by this point that now goodness feels like the distraction.

|

| "I'm sorry, I can't come over there, I have to yawn my way through another soul-crushing party." |

And now the film's core themes become clear. Fellini's film is in no way preachy, nor does he say, "I have a simple answer that solves everything." In fact, the entire film can simply be read as an indictment against modernism in late 1950's Italy, if that's as far as the viewer chooses to go, looking past all of Fellini's symbolism and metaphors.

|

| "Please, the Nicsperiment, please just say a cigar is just a cigar!" |

However, those metaphors and symbolism are undeniably here. Fellini gives great examples of what choices NOT TO MAKE with Marcello. However, he also gives subtle hints as to what choices should be made to live "the good life," hints which become more explicit by the film's final moments. Throughout La Dolce Vita, Marcello continually makes choices that immediately meet his base desires, continuously starving his loftier ambitions and aspirations. For all intents and purposes, he is the crowd he observes, chasing after the fast and easy miracle in the film's fourth episode in the form of every quick and easy fix close to hand. However, as the priest says, "Miracles come from pious meditation, from silence." They take work. They take patience. At the end of La Dolce Vita, Marcello is presented with a true miracle in the reappearance of Paolo. Marcello has lived his whole disappointing, sad excuse for a life to reach this moment. All he has to do is walk 50 feet through ankle deep water.

It's too much.

He won't do it.

He won't do it.

|

| I can't express how tempted I am to hyper analyze the color choices in this scene, but for now, I'll resist |

Is La Dolce Vita still my 4th favorite film? YES! It doesn't quite creep up on my top three, but the other films I'm planning to revisit throughout the rest of this year will have to do a lot more than walk 50 feet through ankle-deep water to supplant it from this spot. Considering Fellini's incredible direction, the stunning and spellbinding visuals by cinematographer, Otello Martelli, Nino Rota's jazzy, incredibly engaging score, incredible performances by everyone onscreen, Leo Catozzo's top-tier editing, and a script that redefines perfection, that estuary might as well stretch for a million miles.

Comments